The Federal Reserve seems to be getting what it wants – for housing at least.

Rising mortgage rates slowed home buying at the end of last year, driving down home prices nationwide.

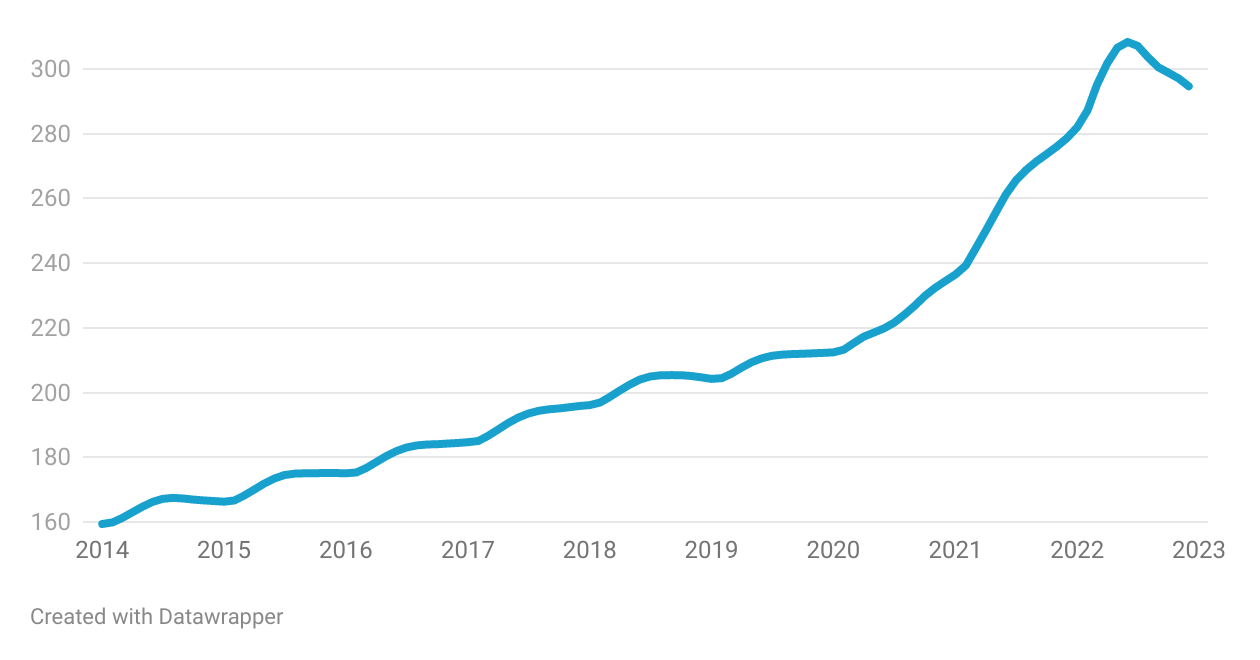

Seasonally adjusted housing prices fell 0.8% in December and were 2.7% below the peak last June, according to the monthly S&P Case-Shiller Index released on Tuesday. December marked the sixth straight month of price declines, an important milestone in the Federal Reserve’s ongoing effort to combat inflation.

The slowdown in prices is the direct result of higher interest rates, which make homes harder to afford and drives down demand. The Federal Reserve has raised interest rates eight times in the past year, and mortgage rates followed suit, surging to 6.88% in February from 3.22% at the beginning of 2022.

The recent pullback represents a dramatic six-month reversal of the surge in demand during the pandemic. December’s prices were still 5.6% higher than the same time in 2021, but the pace has dramatically slowed: the annual increase in November was 2 percent higher at 7.6%.

Renters caught a break too. According to Zillow estimates, rent prices had the slowest gain since May 2021.

All 20 cities measured by the Case-Shiller Index experienced a month to month decline – but not at the same rate. The San Francisco market, for example, saw an annual decrease of 4.2% where Miami experienced an increase of 15.2% in the same time period.

Regardless of these variances, experts say the country shouldn’t expect these declines to reverse course any time soon.

“These prices probably aren’t at the bottom yet” said Oscar Munoz, the Vice President of US Macro Strategies for TD Securities. “The Fed has not indicated that they are going to stop raising interest rates, we can expect these prices to keep falling.”

Other housing metrics support Munoz’s prediction. New mortgage applications reached the lowest levels recorded since 1995, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association.

The Fed has had less success in manipulating the cost of labor and consumer spending as a mechanism for addressing inflation. In January, unemployment reached its lowest level since 1969, suggesting that an already tight employment market might continue to drive up the prices for goods and services.

December’s numbers demonstrate that the Fed’s influence on the housing sector continues to be significant, but no one should expect headlines celebrating low inflation just yet. The Fed is able to target housing prices first most efficiently, but it’s influence is slow: the Consumer Price Index is calculated using a weighted average of six months of prices, which means the prices from the peak in 2022 are still influencing the inflation rate, creating a lag.

Although the prospects of a recession remain uncertain, experts are optimistic that the precipitous drop in housing prices at the end of 2022 will not lead to a repeat of the 2008 housing crisis, based on the sheer home value gains experienced during the pandemic. Housing can have a market-wide impact due to its influence in tangential markets like construction and manufactured goods. In spite of the last six months of decline, 2022 still experienced a 15% price gain in house prices.

“The typical homeowner is sitting on a lot of equity right now. It’s a very different kind of situation than it was during the 2008 housing bust,” said Jonathan Millar, a senior economist for Barclays Capital. “Really there’s a lot of equity – it’s not like people bought their house pre-pandemic or in danger of not being able to make their mortgage payments right. It’s kind of a different situation.”